A Fast Sucker

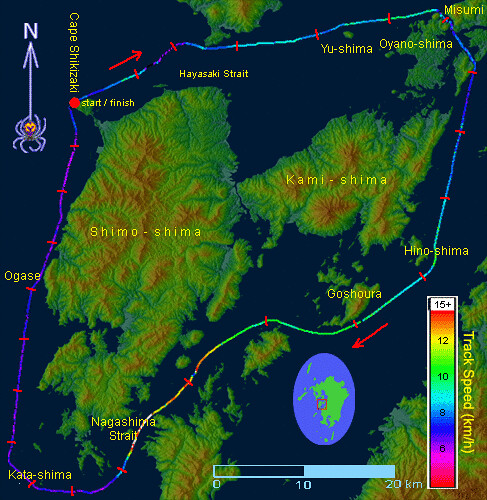

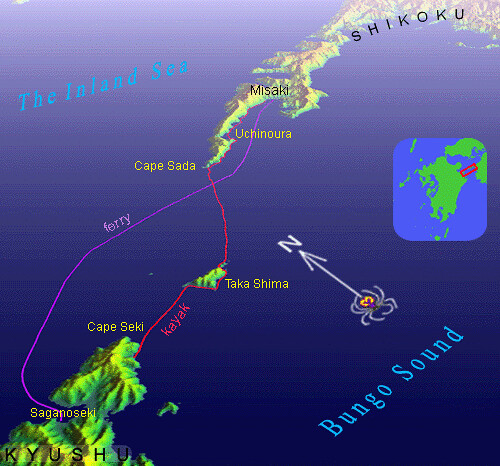

The Hayasui Seto separates Kyushu and Shikoku, two of the main four islands of Japan. It also connects the Inland Sea with the Bungo Sound and hence the Pacific Ocean. Two such large and very different bodies of water do not meet smoothly, and the strait’s literal name, “Fast-Sucking”, bears some witness to this. Well-known as Japan’s ‘skinniest’ peninsula, a 50-km long, but only 1-4km wide finger of land that culminates in Cape Sada on the strait’s northeast (Shikoku) side, forms an enormous natural dike that further concentrates tidal currents. At spring tide, these reach 8 knots, so that even ocean-going ships experience some trouble passing through. Violent eddies, haystack waves, and other phenomena are common. Under such conditions a kayak would surely get swept away like a toothpick down a storm drain.

It was therefore wise that we chose a neap tide, and a calm day, to make this exciting crossing ourselves. There was an ulterior motive: we were delivering a special-order, 3-person kayak custom made by Water Field for a Mr. Sugimoto, a Shikoku kayak guide of some renown. Mr. Sugimoto was to ride the ferry to Kyushu to take part, and the man in charge was none other than our good local friend and kayak guide Kenji Suemitsu. With Leanne and I that made four, so I took this opportunity to take the Hayate I’d used on my Amakusa circuit for another spin. But would I be able to keep up to such an ably crewed triple? In particular Mr. Sugimoto’s reputation as a Herculean paddler preceded him across the straits.

On Sunday, Leanne and I made the 5-hour drive across Kyushu, passing on the way through the enormous ancient crater of Mt. Aso, Kyushu’s premier tourist destination. (The volcano still churns and occasionally hurls smoking boulders into the crowded parking lots.) In the late afternoon we reached Honjo, one of our favorite climbing areas, sporting limestone so steep that one makes more horizontal than vertical progress climbing here. My arms and back were still not recovered from last Wednesday so, needless to say, my performance in a powerful place such as this left a lot to be desired. We promised ourselves we would come back soon in spite of the distance.

In the evening, we drove on another hour to the industrial town of Saganoseki where we met with Kenji at a nearby beach and parking lot that was to be the tour's departure point. Mr. Sugimoto, a swarthy and energetic man in his early thirties, arrived on the late evening ferry and was shuttled in by Kenji. After a beer or two we all retired to our tents and slept rather hard until dawn.

In the morning, we spotted a car at the ferry terminal, and got the boats ready. As soon as the triple was afloat it took off eastward at eyebrow-raising speed. Yours truly in the Hayate, straining as he might, was not gaining any ground in their wake. To wit, Mr. Sugimoto, head down in the bow seat, was spinning his paddle like a windmill. Only on the rare occasion when he took a break was I able to catch up. Glancing at the GPS revealed a shocking truth: we were hydroplaning toward Shikoku at 10-11 km/h! The triple could probably circumnavigate Shikoku like this, but how long could I keep this up?

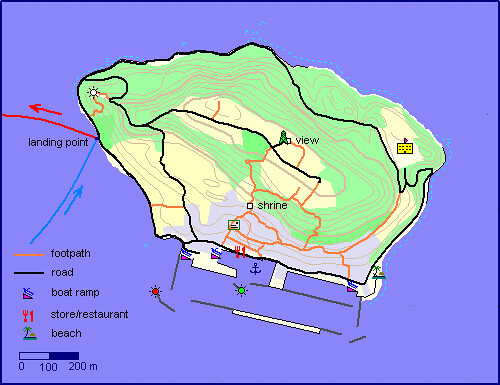

Hardly 30 minutes went by and we were alongside the shores of Takashima, a dramatic and scenic island still on the Kyushu side of the main strait. Sweating profusely, I was hoping for a break at a nice beach that presently came into sight, but it was not to be: the triple steamed on along the coast. Passing a rocky cape, I swerved through a narrow gap in the rocks while they cut a wide arc along the outside, briefly surrendering their lead. But I didn’t even have time to wipe the salt and steam off the camera lens to profit from my only chance to take a head-on picture of them.

At the east end of Takashima, land gives way to the sea in a series of steep rocky islets riddled with caves, cliffs, and narrow passages. This is the kind of seascape that every kayaker looks and hopes for along his travels. This morning, several thousand noisy seagulls dotted the water and rocks, or swarmed in the air like insects. Masses of yellow flowers matted the ledges of the cliffs. Even the triple slowed to a glide, its crew enjoying the spectacle.

A lighthouse perches on the very last rock of Takashima, marking the western limit of the waterway to the hundred or more of oceangoing vessels that pass through the strait each day. It is 8km to the lighthouse at Cape Sada on the other side. As expected, once on open water the triple resumed its express speed. In the interest of staying reasonably together, I am sure they had to wait for me occasionally, but I was finally finding my own rhythm. Additionally, my boat had an easier time surfing on the occasional standing waves, and in such places our speeds were matched. We snuck through a lucky gap in the shipping traffic, having to wait only once sandwiched between a ferry and a freight ship who were themselves busy avoiding each other. We also had significant current against us but even so we made it across in just over an hour. Steep scenic cliffs ringed the cape, and we admired these as we motored along ever forward.

The triple nears Cape Sada in current-induced standing waves.

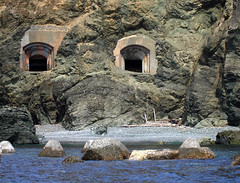

Old cannon emplacements at the westernmost point of Shikoku.

Finally, we pulled up at the beach near the village of Uchinoura. We enjoyed a relaxing break while Mr. Sugimoto distributed packages of PowerBar gel, a luxury we hadn’t tasted in a long time.

From here, I decided to head back. I wanted to land and walk around the trails near the Sada lighthouse, visit the remains of the WWII artillery installations we had spotted on our way in, and still have time to get back to our starting point just as Leanne and Kenji would be arriving there by ferry and car.

After a hearty wave good-bye, Mr. Sugimoto again put paddle to water and the triple was off. Within minutes they were just a speck on the sea, dwarfed by the 19 wind turbines stuck into the spine of the narrow peninsula beyond them.

Enjoying the excellent boat I was in, the beautiful scenery, a good tail breeze and favorable current, I cruised back along the coast, passing on the way a reef curiously named Hakase-Baya, or Ph.D. Rock. I wondered what historical character this name honored in an inhospitable place like this. Probably he was a misfit and a wanderer like myself: a kayaker and ad-hoc English teacher with a doctorate in theoretical physics.

Walls of beautiful green gneiss towered along the coast, riddled here and there with caves I explored, careful not to scratch the borrowed boat.

The Water Field Hayate in its natural environment.

After a tricky landing at the cape, I walked the trails and enjoyed the views. Surprisingly, the steep up-down trail was teeming with tourists also eager to visit the lighthouse, the trail’s exertions visible plainly on their exercise-starved bodies.

Looking towards Kyushu across the Hayasui Strait. Taka-shima is visible; to its right Cape Seki can just barely be made out on this somewhat hazy day. Shipping traffic into ports such as Shimonoseki, Kobe, and Osaka is heavy through through these waters.

Soon I was off again, back across the straits to Kyushu. Once on the open water, I found I was pushing myself again as if following the triple. Maybe I had become infected by Mr. Sugimoto’s attitude. He says he has a need to work off extra energy, being too healthy: he never gets tired and has never even so much as caught a cold in his life. Incidentally, he had ordered the triple so that he can shuttle tourists around the water two at a time, like a kind of water-rickshaw. He is lucky having found work that seems a perfect match for this character.

At Takashima, all the birds we had seen earlier had all disappeared. The ferry Leanne and Kenji were riding on was plying the water in the distance, and we made radio contact with our walkie-talkies. I made quick work of the final crossing. Another perfect and enjoyable day was complete, and after a dinner of udon noodles at a roadside restaurant, we were ready for the long haul back home.

Mr.Sugimoto also wrote a report about our crossing, for a different perspective and text in Japanese, please refer to his homepage.